Many Center Grove parents find themselves in a similar scenario. Your child became an avid reader before ever taking that first step into his or her kindergarten class. After all, you read with him every night, paid tuition for a great preschool, and provided enriched background knowledge through family vacations and trips to the zoo, children’s museum, religious study, and just about anything else you could let him experience. How in the world will the public school (as you remember it) ever challenge your child? Will he ‘go backwards’ as he sits at his desk, staring and waiting for his classmates to learn the letters and their sounds?

Chances are, other parents are meeting with their child’s future principal and posing these same questions. And the principal might be thinking about loosening his tie and responding with, “This just ain’t the kindergarten you remember.” Educating children and helping their parents support them is just too important for that kind of answer. That is why you are likely to hear something like, “Our teachers are wonderful at differentiating instruction, and I am confident they will meet your child’s needs.” What exactly does that mean?

Educators tend to speak with a lexicon of learning and sometimes do not catch themselves withholding the translation of the research (i.e., educational jargon) they spend so much time learning on Early Release Wednesdays and other professional development. Do not hesitate to ask them to pause and clarify things like “differentiated instruction.” This is your child, and not an ounce of humility is necessary. Just ask.

ASCD (formerly known as the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) has a website devoted to the lexicon of learning (located at ascd.org and search for “lexicon” in the search field). When teachers or principals tell you they “differentiate instruction,” they are telling you they: a) use an intentional method to find out the academic levels of each of their kids; b) spend time observing and interacting with each child to find out his/her interests and preferred ways of learning and expressing himself/herself; c) adjust their lesson planning and content to meet those “needs” in a way that maximizes each child’s academic progress; and d) evaluate how that worked for each child by again measuring those academic levels. While this article focuses on kindergarten, teachers differentiate instruction by following these steps at all grade levels.

Why Do Teachers Eat Lunch With the Children?

The assessment of needs likely began weeks or even months before instruction began. The “kindergarten screener” your child took shortly after registration gave the school initial information regarding academic skills such as who knew their letters, who did not know their letters, who was reading, and who was reading chapter books. That information was used to strategically place students in classrooms.

Teachers in all grade levels conduct a continuous cycle of measuring and understanding student needs throughout the whole school year. They use interest inventories and spend time eating lunch with their students to find more about how they can relate their learning to what motivates them. Teachers also give pre-tests to determine entry levels of specific topics, subject matter, skills or tasks. In the early grades, reading is a primary focus and is constantly being assessed and tailored to the student.

Center Grove elementary schools use Guided Reading Levels (GRLs) to assess student-reading readiness and continue to promote student progress in literacy. These GRLs are measured using the alphabet, with “A” being the beginning learner and “Z” being the highest level in elementary education. To progress through the levels, students have to demonstrate that they can read the passage for that level with accuracy and retell the main ideas of what they just read. Kindergarten students are expected to reach a GRL of “D” or beyond by the end of the year. Some students actually enter kindergarten at “D” or higher. At the same time, some students who enter kindergarten do not recognize letters or their sounds.

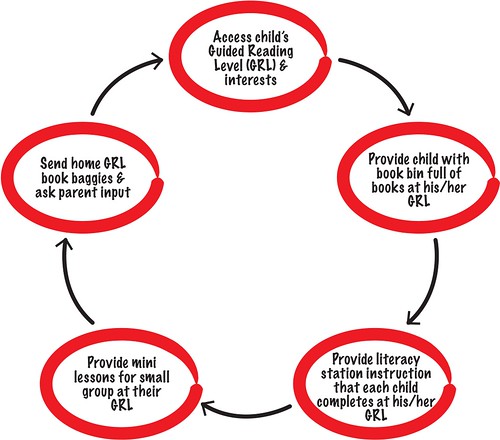

Varied reading levels have become the norm in nearly all schools. Teachers at all grade levels expect this; they are prepared for it and they deliver the necessary individualized instruction without even batting an eye. Following the cycle in Figure 1, teachers create leveled reading station groups and mini lessons. Their classrooms have bins of books that are sorted by GRLs.

Each student completes reading stations with text at his or her individual GRL. During these stations, the teacher provides mini lessons to small groups at the teacher table. Some of these groups are reading texts beyond the year-end Kindergarten goal (GRL “D”), and they have new goals such as the end of the year first grade goal (GRL “J”). Students at all levels practice literacy that is individualized for them, and their teacher has structured the classroom in such a way that enables him or her to teach differentiated mini lessons while also increasing the time students have practicing with a curriculum that is rigorous for them. Teachers also send home leveled book baggies each week and ask parents to sign reading journals and share their opinions on whether or not the reading is too easy or too hard at home.

Figure 1 The Continuous Cycle of Differentiated Reading Instruction

Meeting various readiness levels in math is very similar. Students are given common math assessments, and differentiated math stations and mini lessons are provided. Students are also assessed on their math facts and moved through addition, subtraction, multiplication and division at their own pace. In addition, each student in grades K-2 has his or her own iPad, and they are provided with apps that assess and provide rigorous activities at individualized levels.

How Do You Define Challenge?

When discussing how your child is challenged at school, it is important that you and the teacher and/or principal are speaking about the same thing. How do you define “challenge?” Is it acceleration of the curriculum, meaning teaching your child the next topic or standard? Is it having your child learn or perform at a deeper level of knowledge, such as being able to teach the concept to his or her peers or create something based on the application of that knowledge? Is it both? Center Grove Community School Corporation identifies “challenging” students as both enhancing the depth of knowledge and the breadth of knowledge.

The aforementioned reading and math examples exhibit a glimpse of how teachers extend the breadth of knowledge. Teachers also ensure individualized growth and success through authentic learning experiences such as flexible assignments that encourage creativity, student choice assignments and rigorous lessons that involve participation at a greater depth of knowledge.

For example, classes do not just take a field trip to the zoo because it is the fun thing to do. They build upon such trips in ways such as having students pick two animals and create a presentation on their similarities and differences. They might also learn about recycling and then be challenged with inventing something new with recycled materials. Another example includes having students read something at their reading level and then critique what the author said and/or add what they would have written instead. Teachers also offer authentic learning experiences through technology, such as iPads (in grades K-2) and Chromebooks (in grades 3-5).

What You Should Know & Questions You Can Ask

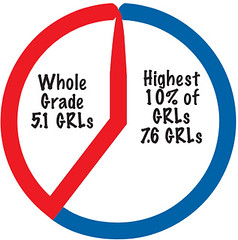

Challenging the depth and breadth of knowledge of children is a very complex topic. It is something that is not taken lightly, and schools intentionally plan for it. Figure 2 shows data from one Center Grove school, Sugar Grove Elementary, which exhibits that teachers not only plan for challenging the knowledge of students, but they are also successful at it. While this data and article has focused on primary students, you should know that schools also intentionally challenge the older students, as well, and that data supports their efforts.

Figure 2 Average Increases in Guided Reading Levels for 2013-2014 School Year at Sugar Grove Elementary

Figure 2 Average Increases in Guided Reading Levels for 2013-2014 School Year at Sugar Grove Elementary

During the 2013-2014 school year, students scoring in the top 10 percent of Guided Reading Levels averaged an increase of 7.6 Guided Reading Levels in kindergarten and an increase in 5.7 Guided Reading Levels in first grade. This shows that students scoring in the top 10 percent of literacy readiness at both grade levels increased as much as or even more than the rest of their grade level and were successfully challenged to continue making progress. Students who scored at or near the top in the beginning of the school year remained there through the end of school.

Parents can support the efforts to provide rigorous educational experiences for their children by asking the right questions. You might want to ask such questions as, “How do you measure my child’s reading/math progress?” “How do you know my child has made progress?” “How can I help at home?” and “How does this information relate to what is noted on my child’s report card?”

A Word on High AbilityThe State of Indiana Academic Code requires schools to identify “High Ability Students” and provide programs for them. Center Grove Community School Corporation goes beyond differentiating in the regular classroom to meet this state requirement by offering Extended Learning classes to the top 7 to 10 percent of students district-wide at grades 4 and 5. Enrich Classrooms are also offered at grades 1-5 to students who are among the highest achieving academically.

Some parents have opted out of these opportunities when their children have qualified for them and have been pleased with the differentiated instruction in the other classrooms, while other parents have been disappointed when their child has not qualified. (You can learn more about Extended and Enrich Learning by contacting the school or online at centergrove.k12.in.us/highability.) However, it is important to realize that there is a difference between high ability and being highly prepared.

In the primary grades, it is difficult to tell the difference between students who truly have a higher academic ability and those who are achieving at higher levels because they have been so well prepared for their educational experiences. Third grade is typically the year when those who were not as ready for school but truly have a high ability for academics tend to catch up with their peers who were more prepared. The ‘playing field’ tends to ‘level off’ that year, and students’ true cognitive abilities are more accurately measured.

A Final Thought

Please read with your children every night, understand their instructional level and how you can support their progress, and continue to provide enriched background knowledge through family outings and just about anything else you can let them experience. You know the right questions to ask, and can be proud knowing your child is working hard at school on a rigorous curriculum that has been designed specifically for him or her.

Figure 2 Average Increases in Guided Reading Levels for 2013-2014 School Year at Sugar Grove Elementary

Figure 2 Average Increases in Guided Reading Levels for 2013-2014 School Year at Sugar Grove Elementary