Writer / Janelle Morrison

Traversing through the county roads in northern Hamilton and Boone County, Indiana, one could easily pass by without knowing the epic history of the land they are cruising through. For instance, a lone white chapel that sits on a parcel surrounded by farms marks where a vast, free black settlement once dominated upwards of 2,000 acres of that part of the county.

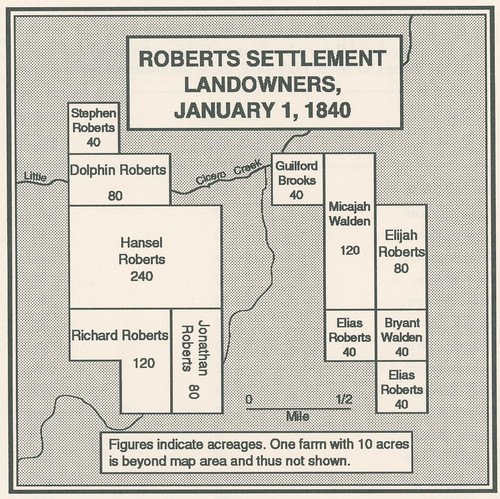

In 1835 African-American pioneers Elijah Roberts, Hansel Roberts and Micajah Walden purchased homesteads in northern Hamilton County, 30 miles north of Indianapolis, Indiana. Land was fertile and affordable at $1.25 per acre. The families of these men settled permanently on these homesteads, establishing what would be known as Roberts Settlement. By 1840, Roberts Settlement was home to approximately 10 families and 900 acres of land that neighbored Quaker homesteads. These early pioneers purposely settled near Quaker establishments, as they were known to be accepting of free blacks and were supportive neighbors.

The families of Roberts Settlement were people of mixed African, Native American, and European descent. They had lived in eastern North Carolina as free landowners prior to the American Revolution. In fact, many of these men served in the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War. As slavery became more prevalent in the United States and racial tensions ensued in the 1800s, the free blacks were subjected to harsh treatment and suspicion from the white landowners and steadily their rights would become jeopardized.

Dr. Stephen A. Vincent, a Hamilton County, Indiana, native and author of Southern Seed, Northern Soil, has conducted extensive research on the history of Roberts and Beech Settlements in Indiana. His book is a combination of 20 years of research and interviews with descendants of the Roberts and Beech Settlement families. A documentary based upon his book has recently been produced and is currently being screened by historical societies and related organizations. Many Roberts Settlement residents first settled in the Beech Settlement in Rush County, Indiana, prior to moving north to Hamilton County. Dr. Vincent described the deteriorating conditions and the impending threat to the free blacks’ freedom that prompted them to gather their belongings in ox-pulled wagons, amid the unknown perils along the path to the north.

“By the 1820s, conditions had gotten to the point where it was becoming increasingly difficult to make a living because of the lack of tolerance of most whites around them,” Dr. Vincent explained. “The only thing that separates the free blacks from slavery is a legal piece of paper that indicates that they are free. However, an unscrupulous white could simply take that document and rip it up and move them to three or four counties over where nobody knows them and sells them as slaves.” You may have seen a depiction of this on the big screen in the Academy Award–winning movie, Twelve Years a Slave.

In 1831, the Nat Turner Rebellion, one of the three largest and most violent slave uprisings, occurred within 100 miles of their homes. Elijah Roberts, Hansel Roberts and Micajah Walden decided it was time to lead their families to the northern frontier and re-establish their lives in hopes of prosperity and safety.

The formative years of Roberts Settlement were not spared any challenges. The nation suffered an economic downturn and depression that lasted from the late 1830s through the early 1940s, stifling the early development of the settlement.

As the nation’s economic health improved, the growth of the settlement increased. By 1850, there were 16 families and 112 residents. While relations with their neighboring Quaker families were favorable, the degradation and intolerance from “outsiders” intensified as negative views of African-Americans were propagated and the nation became divided over slavery. The State of Indiana ratified its constitution and passed Article XIII that prohibited further black settlement within the state. Although the Roberts families were vulnerable to the intolerance of people outside of their community and were keenly aware of the possibility of kidnappings and angry mobs, the families would persevere and enjoy an era of prosperity from the 1850s through the 1870s. The opening of the Peru and Indianapolis railroad line in 1853 provided easier access to markets and a litany of products to the families. New farm equipment was purchased, and stick frame houses replaced the early log cabins, amid a civil war that was testing the nation’s resolve during 1861 through 1865. Legislators repealed the state’s most restrictive racial laws, granted voting rights to African-American men and provided funding for African-American schools.

In the late 1870s, Roberts Settlement included 300 residents and had acquired approximately 2,000 acres of land. The Roberts families had embraced their neighboring Wesleyan religion and became part of the Wesleyan circuit that included several area churches, often worshiping and teaching along with their white neighbors. A school was erected after 1870 and a white clapboard building with a steeple replaced the settlement’s earlier log chapel in 1858. The community was well known for its middle class ideals and emphasis on moral improvement, refinement and respectability. Residents William Roberts and Elijah Gilliam were the first to become politically involved in their local Republican Party and were elected as township constables. Elijah Gilliam was the son of Moody Gilliam who was the first free black to settle in Boone County, Indiana. Their settlement was on the border of Marion and Union Township, east of Lebanon. Moody’s daughter, Sarah Jane (Moody) Walden, was the first free black child born in Boone County and she married Peterson Walden, son of Micajah Walden, co-founder of Roberts Settlement. Moody was well known throughout Boone County and was highly respected by his neighbors and friends. At the time of Moody’s death in 1884, he had 21 children, 41 grandchildren and 5 great-grandchildren, of which many settled in either the Roberts or Beech Settlements in the surrounding counties.

In the late 1870s, Roberts Settlement included 300 residents and had acquired approximately 2,000 acres of land. The Roberts families had embraced their neighboring Wesleyan religion and became part of the Wesleyan circuit that included several area churches, often worshiping and teaching along with their white neighbors. A school was erected after 1870 and a white clapboard building with a steeple replaced the settlement’s earlier log chapel in 1858. The community was well known for its middle class ideals and emphasis on moral improvement, refinement and respectability. Residents William Roberts and Elijah Gilliam were the first to become politically involved in their local Republican Party and were elected as township constables. Elijah Gilliam was the son of Moody Gilliam who was the first free black to settle in Boone County, Indiana. Their settlement was on the border of Marion and Union Township, east of Lebanon. Moody’s daughter, Sarah Jane (Moody) Walden, was the first free black child born in Boone County and she married Peterson Walden, son of Micajah Walden, co-founder of Roberts Settlement. Moody was well known throughout Boone County and was highly respected by his neighbors and friends. At the time of Moody’s death in 1884, he had 21 children, 41 grandchildren and 5 great-grandchildren, of which many settled in either the Roberts or Beech Settlements in the surrounding counties.

By the turn of the last century, opportunities at Roberts Settlement were diminishing like many other rural communities and the population had decreased by half. Only 150 residents occupied the Settlement in 1900 and less than 50 by 1920.

Many of the residents pursued higher education and professional lives outside of the settlement. Many became ministers, educators, or doctors, and gained local or state recognition, often holding high positions within their professions. Reverend Cyrus W. Roberts served 50 years as a Wesleyan, and later, an A.M.E., minister in the Midwest. Dr. Carl G. Roberts was a prominent surgeon in Chicago and was president of the Negro Medical Association; and Reverend Dolphin P. Roberts became the nation’s highest appointed official as Recorder of Deeds.

In the 1920s, former Roberts Settlement residents organized annual homecoming reunions as a way to preserve the heritage of the Roberts families. Residents gathered at the settlement close to the 4th of July holiday to reminisce and worship together, a tradition that continues today. The Roberts Settlement will be celebrating its 90th Roberts Settlement Annual Homecoming celebration this 4th of July weekend. Descendants of the Roberts families from all over the country will congregate and celebrate their families, values and history.

In the 1920s, former Roberts Settlement residents organized annual homecoming reunions as a way to preserve the heritage of the Roberts families. Residents gathered at the settlement close to the 4th of July holiday to reminisce and worship together, a tradition that continues today. The Roberts Settlement will be celebrating its 90th Roberts Settlement Annual Homecoming celebration this 4th of July weekend. Descendants of the Roberts families from all over the country will congregate and celebrate their families, values and history.

Paula Gilliam, a Noblesville resident and president of Roberts Settlement Homecoming and Burial Association, established in 1924, discussed the upcoming Homecoming’s program and its importance.

“They always met as a family after church and had gatherings way before it became an official homecoming,” Paula said. “Friday night is the start of the homecoming celebration. We’ve had well over 100, almost 200 with the kids and their parents. This should be a special year because the 4th of July is on a Friday. This year we’ll start at 6:30 p.m. and show the documentary to the people who haven’t seen it yet. At 7 p.m. we’ll have hayrides and a weenie roast. For the last 43 years we’ve also had fireworks.”

Saturday they have a golf outing and start gathering around 1 p.m., then they will eat together and reminisce. They have a program where they talk about who’s passed on and family announcements. Sundays they close with a church service at 9 a.m. and have blessing.

“It’s ingrained in our blood and we’ve got to keep it up,” Paula said. “We’ve heard it and lived it through our parents. I promised my dad that as long as I’m living, we’ll keep this going and teach our kids and next generations after us, that t hey have to keep this going.”

hey have to keep this going.”

Tonja White Goodloe, Carmel resident and a descendant of Roberts Settlement, recited from a letter written by her great-grandmother, Alzadia Roberts Windburn: “To all I would say, be inspired with the legacy left to us by our ancestors. We are doing a great work and we cannot come down. May we go forward to attain a higher realm of life and at last, reach the end of a perfect day.” Tonja concluded, “I think that sums up what each of us has responsibility of doing: carrying on that legacy and passing on that important history to the generations beyond us.”

Teresa Newsom Granger, from Noblesville, commented, “Even at my age now, it has become much more significant to me. For the first 16 years of my life, I lived here. The church was the community for me and to those who lived here. We remember the good times and the kids we grew up with and went to school and church with. Those you didn’t see but once a year.”

The second oldest living descendent, Maize White Glover of Noblesville, recalled that she didn’t care much for country life and had little to no appreciation for visiting the settlement until after she was older. “I had to come,” she recalled humorously and reluctantly. “I wasn’t happy about it—this was the country to me and I was a city girl. After I graduated high school, I went to live with my uncle who was a surgeon in Chicago, but I got so homesick that I only stayed five months. I came home on the Monon every other week and met my parents at the station in Sheridan. I didn’t like living in Chicago; I was just so homesick. After I married and had children, I changed and realized how important and how significant this place here in the country is, but as a teenager I certainly didn’t think so.”

Maize’s son, Bryan Glover, a Noblesville resident who, along with Dr. Stephen Vincent, contributed their research and time toward this article, spoke about his long-term vision and dream for Robert’s Settlement. He worked with Dr. Vincent on the recent documentary. “We’ve had four or five community conversations around Hamilton County with various historical societies like Carmel, Noblesville, Sheridan and Arcadia, and the local libraries, and have screened the film to more than 250 people on those five occasions. We arranged to have a screening at the Eiteljorg Museum and did it as part of their regular monthly meeting for their genealogy group. There were a few descendants of Beech Settlement from Rush County and they had heard about the film and were curious. Now we’ve been able to make contact with part of our genealogy with the Jeffries families who have a strong connection with many of the Roberts people who ultimately came to Hamilton County. We plan on doing this longer film on African- American pioneers and we want to include much more on the Beech Settlement and have been able to make contact with a family.”

Maize’s son, Bryan Glover, a Noblesville resident who, along with Dr. Stephen Vincent, contributed their research and time toward this article, spoke about his long-term vision and dream for Robert’s Settlement. He worked with Dr. Vincent on the recent documentary. “We’ve had four or five community conversations around Hamilton County with various historical societies like Carmel, Noblesville, Sheridan and Arcadia, and the local libraries, and have screened the film to more than 250 people on those five occasions. We arranged to have a screening at the Eiteljorg Museum and did it as part of their regular monthly meeting for their genealogy group. There were a few descendants of Beech Settlement from Rush County and they had heard about the film and were curious. Now we’ve been able to make contact with part of our genealogy with the Jeffries families who have a strong connection with many of the Roberts people who ultimately came to Hamilton County. We plan on doing this longer film on African- American pioneers and we want to include much more on the Beech Settlement and have been able to make contact with a family.”

Regarding the artifacts from Roberts Settlement, Bryan stated simply, “If history isn’t preserved, it’s lost. Artifacts get spread out and get lost, so it seems to me that we should capitalize on the momentum we have and think about how to preserve the history and artifacts we have and how to share them. I have hope that we’ll find a suitable place on Roberts Settlement and put the story together in a way that we can share with the public and find our appropriate place in Indiana and in American history.” To learn more, visit robertssettlement.org.